Recently, Bill Maher did a New Rules segment on his show Real Time to point out the absurdity of the modern-day ‘Deep State’. He asserts that the Deep State is not a shadowy list of actors pulling puppet strings; rather, your next-door neighbor to whom you ask: “What do you do for a living?” and they answer “I am a consultant for the city.”

Bill describes this new bureaucratic class as individuals who justify their existence by making up new rules, and honestly, that is perhaps the best definition of this bureaucratic machine that operates in our modern world. He talks about the famous San Francisco washroom project that had an estimated cost of 1 million dollars; that’s right, a singular washroom costing 1 million dollars to develop. This is to pay all the project managers, construction managers, architecture and engineering fees, permits upon permits, civic design review, surveys, contract preparation, and cost estimation – not to mention all the legal expenses, which is perhaps one of the biggest culprits of the bureaucratic state.

This is not the only crazy story about bureaucratic lunacy, one of my favorites comes from the City of Toronto who commissioned a staircase to be built down a grass hill at Tom Riley Park. The initial cost was $65,000, only to realize retired mechanic Adi Astl, with the help of a homeless man, built a set of wood stairs for $550. Not only did it take the average time of a city project (6 months to a year), it took Astl only a few hours, I’m sure with taking water breaks in between. Unfortunately, the City of Toronto got wind of this and tore the stairs down.

The mayor at the time, John Tory, even said the estimate was “completely out of whack” but eventually rested on the price tag of $10,000. Tory himself, using classic government lines, suggested that although the estimate was absurd, “that still doesn’t justify allowing private citizens to bypass city bylaws to build public structures themselves.” Many of the positions named in the Maher piece about San Francisco came out of the woodwork cited ‘safety and accessibility issues’ even though there is an accessibility path that leads into the park for handicapped individuals to avoid the stairs altogether. ‘City Inspectors’, people who stare at things as a job, called the stairs unsafe because of the railing and the uneven incline – failing to notice the natural hill which spurned the staircase altogether has an uneven incline.

Even some of you reading this right now may see this and say: “Yes, I know it’s absurd and these stories make me chuckle, but we can’t just have citizens taking initiative and building things, willy nilly!” Well, why not? Governments from local to federal want to talk about entrepreneurship and initiative with its populous as a positive thing, but it is not about actually getting people to be entrepreneurs, it is about creating programs and commissions about entrepreneurship to pander to voters. For the sake of argument, let’s address some of the concerns people will have about this staircase.

Q: What if someone injures themselves, especially someone with accessible needs, going down the stairs and sues the city for negligence?

A: The park already has access to people with disabilities, and humans have the freedom to choose what method they want. If an individual feels that the stairs pose a risk, take the alternate route.

This is a question that relates to a legal concept of tortum negligentia, or negligent tort, where the harm caused by failing to act is a form of carelessness possibly with extenuating circumstances. Is that the case here? Would the City be held liable for the stairs even being there in the first place? Must the stairs uphold a ‘duty of care’ for the citizens? Were the risks foreseeable with taking the stairs? Were there alternatives to the stairs to avoid a remoteness clause, meaning the stairs were the only form of transport? Most lawyers would say: yes, absolutely this is negligence, and courts would most likely agree. But I would like to think there could be a defense here based on extenuating circumstances.

- Voluntary assumption of risk: The person with disabilities had a path to take to the park, they did not need to take the stairs.

A reach? Maybe? Let’s use another example substitute the person with disabilities for drunk teenagers who take the stairs, and fall based on the stairs being uneven. Sure, it can be the fault of the stairs, but drunk teenagers fall under the concept of contributory negligence. Perhaps a more solid case.

- Contributory Negligence: The teenagers contributed to the negligence by being drunk (if under 19, illegally) and not taking precautions against an assumption of risk.

I think the bigger question is what is the need for all this legalistic bureaucracy? As I mentioned previously, it is the legal aspect that is perhaps the biggest culprit of the bureaucratic arm. The main question you must ask yourself: Are these bylaws and other legal inputs here to protect or hinder the citizenry? I would still like to think most fall under the protected category, but many fall under the hinder category, with the false sense of protection. Here are some examples:

- Alabama: No stink bombs or confetti – assuming destruction of peace?

- Delaware: Trick or treat curfew – to prevent mischief of any sort.

- Illinois: No ‘fancy’ bike riding – no shenanigans like not holding on to handlebars.

- Maryland: No cursing while driving – I would get life w/o parole in Maryland.

Most of these are absurd, but I think some can find a justification such as odor disturbing individuals in a civil society, mischievous activity like egging a house can be destruction of property, shenanigans can lead to an ER visit, and cursing…being mean is not nice, I guess? I will say, if you are someone who makes justifications for this, I think you might be the problem with this overly-litigious society that we live in, and it is this over-litigiousness that creates the problem of ever-expanding bureaucracy in our institutions.

The Serious Problem – Bureaucracy in our Institutions is not Meant to Make us Safe, but to Keep the Bureaucracy Going.

I have written about the problem of bureaucratic overreach in institutions of higher learning, and why they are justified. They are justified largely because they create a pathway for more bureaucracy and more justification. Like a negative feedback loop where the process and implementation of bureaucracy has the expressed goal of creating more bureaucracy. For example, DEI bureaucrats were created to help stop the issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in schools. Still, they end up creating more issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion – which is good for them, because it justifies their bureaucracy. These are characteristics of the Kafkaesque Bureaucracy (KB) which is described as a surreal bureaucratic system characterized by absurd and irrational rules, labyrinthine procedures, and a sense of hopelessness and frustration experienced by individuals trying to navigate it. The term is derived from the works of the famous writer Franz Kafka, who often depicted such oppressive bureaucratic systems in his novels and short stories such as The Trial, and The Castle.

The KB has many characteristics that relate to the current bureaucracy, such as the heightening of complexion and confusion replete with many forms and documents – leading to more forms and documents. The lack of transparency to get clear information, such as the City of Toronto not providing a succinct explanation of why the stairs can’t be there, just that citizens are not able to build what they want. The promotion of endless delays, futility, and redundancy – the constant meetings, testimony, surveying, approval meetings, paperwork that leads to more paperwork confirming the previous paperwork, contractors, consultants, and everything else to make a day a job and 20-year process. Not to mention when asking questions about these KB characteristics you are met with an incomprehensible hierarchy with decision-making authority dispersed across multiple levels and individuals who seem to wield power without clear explanations: “I am making this decision about the topic sir, but I am sorry there is nothing else I can do”.

Ultimately, the justification of this bureaucracy by institutions acts as a legal liability shield, not to accept challenges, but to prevent them. Schools implement these safe spaces, and DEI policies because they don’t want to be subject to liability related to them. This fear from the institutions creates a justification for the bureaucracy to keep going – it is essentially bureaucratic terrorism, which does not help people and creates an endless loop.

Back in 2019 when writing my book, The Interdisciplinarity Reformation: A Reflection of Learning, Life, and Society, I began developing a theory of the SOKE, or the Systematic Oppression of Knowledge and Epistemology, to describe how knowledge is undermined by a system behind the scenes but displayed as benevolence to the outside world. It wasn’t until Eric Weinstein’s podcast – The Portal: Episode 18, Slipping the DISC – that developed a connected and well-formed understanding of the SOKE for myself. For those who have not watched this episode, please do, it is one of the best podcast episodes ever created.

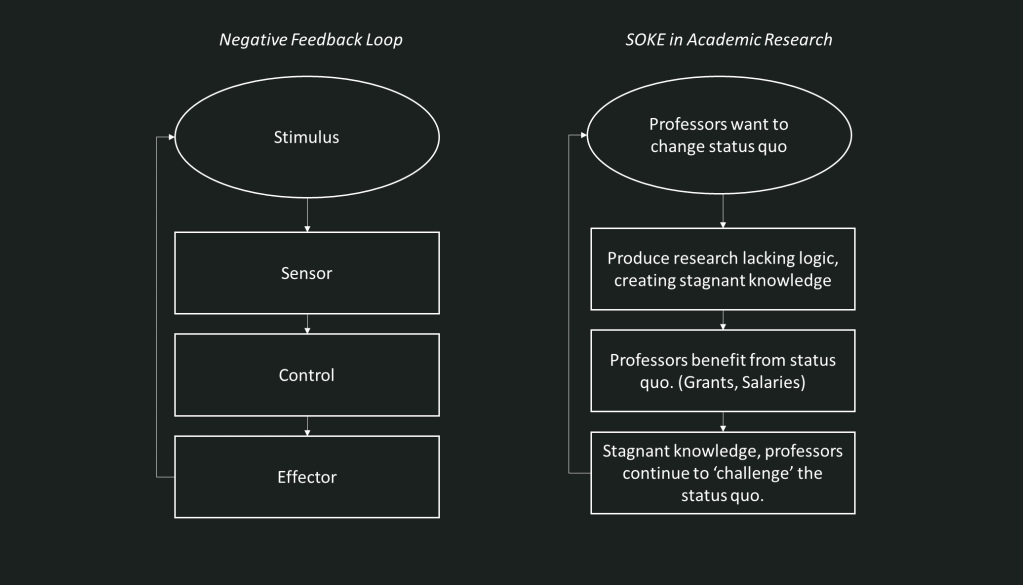

Eric describes the DISC, or the Distributed Idea Suppression Complex, as a process that intends to keep the ideas created by the complex free from any justified and rightful challenge – these ideas of the complex are also coined by Eric as the GIN or the Gated Institutional Narrative. The DISC and the GIN are the sustenance that keeps the KB thriving. Suppression of narratives to avoid challenges keeps the negative feedback loop turning. The DISC and the GIN helped me fully develop the SOKE, which is described as a phenomenon reflected in the policies and administrative levies inside of systems – notably, the college and university systems. It creates a narrative through identitarianism, commonly through research production, to not produce new knowledge, but to maintain the institutional status quo in universities. A visual is represented as a negative feedback loop applied to academic research.

Much like in academic research, we can see KB is the status quo that keeps the SOKE front-in-center in many institutions such as government, corporations, and Global NGOs. The market is not inclusivity, the market is exclusivity of ideas not to enhance knowledge, but to maintain a narrative of knowledge for suppression of most, but not for some. It is essentially turning back the clock and reversing the Gutenberg Revolution by producing knowledge and creating processes that are unnecessary and distraction mechanisms.

***

In closing, I return to the story of Adi Astl and the park stairs in Toronto. I recall the CTV article where they interviewed a resident named Dana Beamon, a member of the public whom the City of Toronto serves, about the stairs being built. She stated that she is happy that the stairs are there regardless of city standards:

“We have too much bureaucracy…We don’t have enough self-initiative in our city, so I’m impressed.”

She is right on both accounts, we have too much bureaucracy and we don’t have enough self-initiative to do things and can make decisions in our own best interests. Unfortunately, this is not a blind spot of the KB, what we see is that it’s an active characteristic of it that promotes the systematic control of ideas and processes for themselves outside of others. The only challenge moving forward is how do we address this?