This is a continuation of my previous work relating to Bertrand Russell and Set Theory, along with Hofstadter’s analysis of mathematical systems. If I may provide a summary of the most recent findings up to this point to give context here.

- Set Theory is a branch of mathematics that deals with the study of sets, which are collections of distinct objects, elements, and properties.

- Set Theory is disputed by Russell’s Paradox pointing out the inherent contradiction that forms when considering the set of all sets {x:x is a set} that do not contain themselves as elements.

- The basis for set theory – unrestricted comprehension – is its primary function; also, its downfall.

- Set Theory relates to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem – that within any consistent formal system that is powerful enough to express arithmetic, there exist true statements that cannot be proven within that system (i.e. within infinite sets, there is always a contradiction: Set Theory and Russell’s Paradox).

- This opens up the possibility that Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem is incomplete.

At the end of the Hofstadter piece, we observed the question, what is infinity? Is it a large pattern or is it something more? We observed the possibility of different infinities and how they could be assessed. What this presents is the concept, not that infinite truth exists, but can it be quantified? This is where Karl Popper’s Falsification Principle is applied to work toward the quantification of infinite truth using a systems thinking approach.

Karl Popper and the Falsification Principle

In 1934, Karl Popper published his book The Logic of Scientific Discovery while he was a secondary school physics teacher. In this work he creates the falsification principle (sometimes called just falsification), which is a doctrine that for something to be considered scientific, it is not tested on how true something is, but how deductively challenge it against false principles. Simply put, can a theory be provably false, if not the theory holds as true. Popper describes falsification as a criterion of demarcation (or scientific boundaries/rules).

“The criterion of demarcation inherent in inductive logic—that is, the positivistic dogma of meaning—is equivalent to the requirement that all the statements of empirical science (or all ‘meaningful’ statements) must be capable of being finally decided, with respect to their truth and falsity; we shall say that they must be ‘conclusively decidable’. This means that their form must be such that to verify them and to falsify them must both be logically possible.” (Popper, 1934, p. 17).

It’s not about how true something is, it is about how false something can’t be to claim truth. This is perhaps a concept that is needed more and more today for good reason, but it seems like a lot of our leadership class, indeed, missed the class on properly assessing truth. Popper also provides a differing view to Humeian (philosophies relating to David Hume) of empiricism. Where Hume was strictly experiential, Popper challenges the problem of experience is that they too can be tested with falsifiability. For example, one can see and experience a war happening in another country but there can be underlying circumstances unknown to an individual that can be deducted through falsifiability. Popper describes it as:

“Problems of the empirical basis—that is, problems concerning the empirical character of singular statements, and how they are tested—thus play a part within the logic of science that differs somewhat from that played by most of the other problems which will concern us. Most of these stand in close relation to the practice of research, whilst the problem of the empirical basis belongs almost exclusively to the theory of knowledge. I shall have to deal with them, however, since they have given rise to many obscurities. This is especially true of the relation between perceptual experiences and basic statements. (What I call a ‘basic statement’ or a ‘basic proposition’ is a statement which can serve as a premise in an empirical falsification; in brief, a statement of a singular fact.)” (Popper, 1934, p. 21).

What this presents is that singular, empirical statements are not as empirical as one might expect; however, singular, empirical statements become claims of truth tested by falsifiability. Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell once said, “War’s not black and white; it’s gray.” This in itself is a Popperian analysis of a war being shown without underlying circumstances happening that either proceed the present or implicate the future.

This leads us to the question of what is truth? I don’t know if a simple blog from some guy can answer a centuries-old question, but we have shaped and coordinated the definitions through the years, and consistently finding contradictions and new ways of observing truth. With that said, there are basic routes of understanding for truth, from Plato’s dialogue with the Sophists to Pontius Pilate in the Roman Senate, to the Enlightenment empiricists of Bacon, Descartes, Locke, and Hume, to the current iteration of Set Theory, Russell’s Paradox, Gödel, and Hofstadter. I truly believe it is within this concept of falsifiability, that we can conceptualize truth better than past ideas.

Systems Thinking Approach

You may have heard of the phrase ‘systems thinking’ before. Perhaps you’ve heard it in a meeting with your boss saying we need to embrace a systems thinking approach, which in their definition, means a top-down decision-making approach with little recourse for a challenge, much like my previous blog on sustainability and how the many people who use it don’t really understand what it means.

Systems thinking is not necessarily top-down; rather, a holistic approach to problem-solving that views a situation as a complex network of interconnected components and relationships. This is opposed to the centralized function of isolation, but finding an objective and independent outcome, based on well-thought-out networks. Ultimately, the primary objectives of systems thinking are to analyze the underlying structures and dynamics of a system to identify the root causes of complex problems, rather than just addressing characteristics. Additionally, systems thinking aims to facilitate better decision-making by considering the long-term consequences of actions and interventions within a system. So, when Vice President Kamala Harris uses “root cause” without any recourse to identifying and facilitating truth is manifested. She is understanding systems theory, probably at the level an ant understands an iPhone.

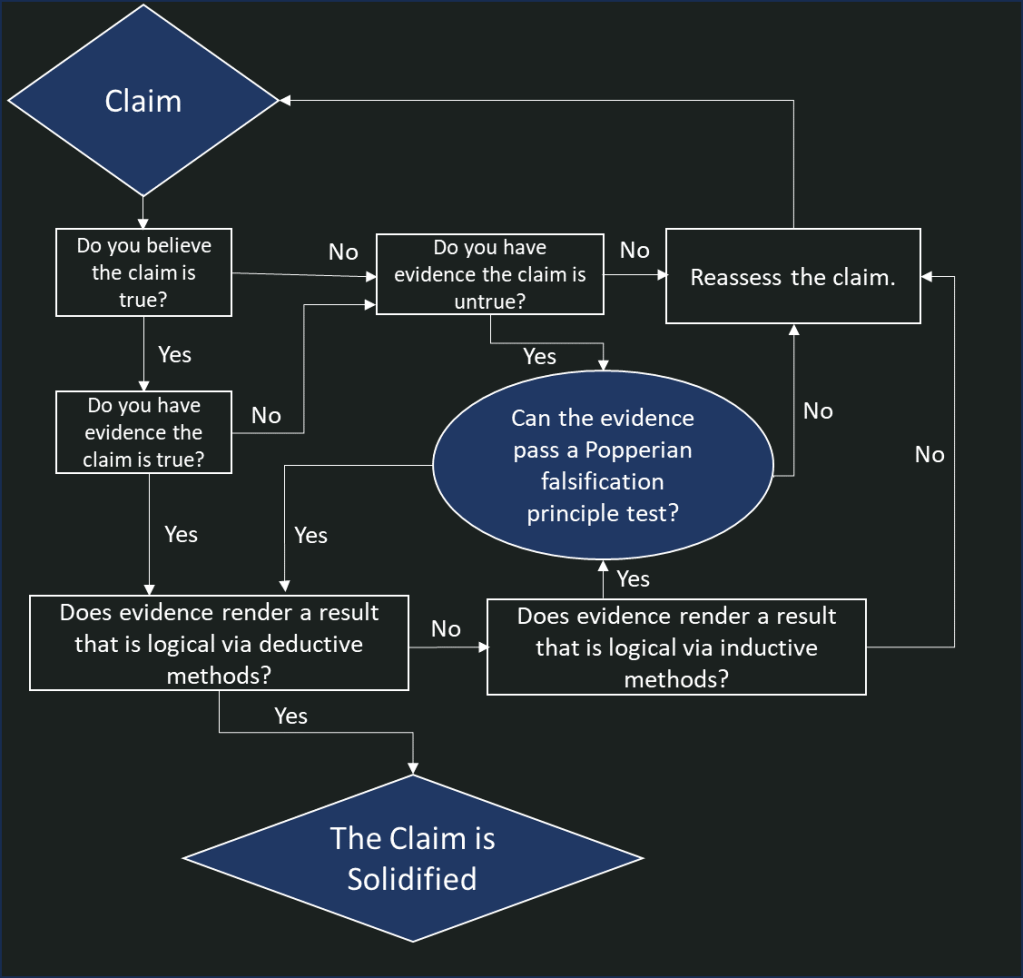

How might this be reconfigured for truth? Well instead of starting with a complex problem, we can start with a complex claim that we believe to be true or untrue. The next stage is finding the evidence related to your decision of truth and does it eventually passes a falsifiability test toward a deductive logical conclusion. If it is unable to do so, the claim must be reassessed. Below is a diagram outlining this path.

Let us use an example here. We can propose a claim that female bears give birth to bear cubs. Do I believe this claim to be true? Yes. Do I have evidence that this claim is true, perhaps I spent a year studying bears, reading research, writing research, field study, etc., and I conclude that all of the female bears I observed, based on the evidence, give birth to bear cubs. It does not end there; I need to form a clear deductive statement about this:

1 – Female bears give birth.

2 – Bear cubs are the result of birth from bears.

∴ – Female bears give birth to bear cubs.

This statement ultimately rests on whether it’s falsifiable, as in, I could say that I can’t deductively assume that bears give birth to cubs, even through extensive research, so the question I ask, is do bears give birth to anything else? Other than a Rhino is Ace Ventura 2 When Nature Calls, in wanting to prove that bears give birth to anything other than bear cubs, I am proven false, that they only give birth to bear cubs. Do male bears give birth to bear cubs = no, I am proven false. Do female bear cubs give birth to alien beings from outer space = no, I am proven false again.

You can see using a biological precedent like female bears giving birth can use a systems thinking approach, but it is outlined for complex problems – and considering the biological reality of the statement, I apologize for putting you through a monotonous analysis. In this case, let’s use a complex problem related to a truth claim. The enhancement of social media and the free internet will make way for misinformation and disinformation hurting democracy. Depending on your stance you may believe that this claim is true or untrue. This is where it gets interesting. Do you have evidence for the claim being true or untrue? If make this claim and believe it to be true, and you don’t have evidence of it being true, you have to look at additional evidence. If you find evidence the claim is to be untrue, you must continue with that, if not you need to reassess the claim.

- Claim: The enhancement of social media and the free internet will make way for misinformation and disinformation hurting democracy.

- Do you believe this claim is true: No.

- Do you have evidence that this claim is untrue: There is a lot of evidence out there to confirm or deny and needs to be continually assessed.

Ultimately, if I cannot provide evidence that the claim is untrue, I need to reassess the claim. I would use continual evidence on the lack of evidence on ‘Russian Troll Bots’ influencing individuals, and that evidence for net neutrality (free and open internet) actually enhances democracy and democratizes the entire internet landscape. Meaning:

- Do you have evidence that this claim is untrue: Yes.

- Can the evidence pass a Popperian falsification principle test: Unclear at this time.

Again, we reach another hurdle, the most important and needed hurdle to assess the evidence’s falsifiability and if it can produce a deductive statement based on it. Of course, I hate to disappoint if this does not produce answers right away, rarely truth is unfounded right away, and needs to be consistently reassessed.

For my final example, let’s use a simple, relatable, but also, complex claim. Masks worked in stopping the spread of covid-19:

- Claim: Masks worked in stopping the spread of covid-19.

- Do you believe this claim is true: No.

- Do you have evidence the claim is untrue: Yes (Cochrane), Yes (significant literature), and Yes (170 studies proven).

- Can the evidence pass a Popperian falsification principle test: Yes (through the extensive research done on comparing the evidence to the perceived evidence of masks working, only to conclude poor studies or the null hypothesis.)

- Does evidence render a result that is logical via deductive methods? Yes.

- 1 – Extensive research shows that masks do not limit the spread of respiratory viruses.

- 2 – covid-19 is a respiratory virus.

- ∴ – Masks do not work in stopping the spread of covid-19.

- The initial claim is solidified as false.

Now, one may disagree with this outcome, but it doesn’t make it any less true, to make their disagreement true they will have to run it through the same process, but eventually with the evidence they will ultimately have to reassess their claim toward the solidified claim.

Conclusion

Continued analysis should be done to assess truth claims, and this is the reason truth claims have been debated throughout the centuries. However, Karl Popper was onto something by re-engineering how we see and assess truth – by not seeking the truth, but by seeking to falsify the claim of truth, failing or succeeding, and making a statement based on the outcome. Even as an exercise in research ethics, you don’t want to consistently confirm your claim, you want to challenge and falsify your claim to ensure no doubt that your claim is solidified. I think we have lost that recently in our ability to find the truth which is at the heart of critical thinking. The need to want to disprove will ultimately render the most accurate outcomes and we can set a course for actual truth.

3 thoughts on “Assessing Truth Claims with Karl Popper’s Falsification Principle as a Catalyst”