Every so often I go back to the Benjamin Boyce’s (@BenjaminABoyce) curation of the insanity that happened at the Evergreen State College in 2017. One thing I can never get over is how the administration just stood there and let students disrespect them, berate them, and take back institutional power over them. As the students yelled in their faces, they just stood there silent and with sorry eyes hoping that the student would just go away back to class or another area on campus. One can look at George Bridges – who was Evergreen’s president at the time – who apologized for his hand gestures being ‘microaggressions’ or fixing teacher training policy on the whims of irrational activists – including Professor Naima Lowe.

Something struck me so familiar with this situation, perhaps why I resonated with so much passion. I looked at these administrators and teachers and wondered why they didn’t just say “Sir, you are being disruptive to the other students here, if you continue, we will have to ask you to leave”. I have said this exact quote before when I was a front office manager in hotels, except I substituted students with “Sir, you are being disruptive to the other guests here, if you continue, we will have to ask you to leave”. That is really when it hit me, I have seen this many times during my work in the hospitality industry, the irate guest who is having a fit that their dry cleaning was not delivered at the right time and the manager or the front desk attendant staying silent waiting for a break in the tirade to calmly offer some form of compensation.

Us hospitality warriors are a rare breed, and it is not for the faint of heart, you need a thick skin to work in this field as you will assuredly be in a situation where a guest blows their top at you. Of course, this is not natural, it is taught and there is a method to it all. First, we are trained to not take anything personally when a guest gets angry as the dry cleaning could have just been one of the many issues during their stay. Second, people who get overly angry over modest things are generally unhappy people, so with this mindset, you almost feel sorry for this person. Third, definitely offer some form of compensation have it be a free breakfast that is 400% markup, or a fancy – not really fancy – bottle of wine (600% markup) to show them of their importance and your apology for the situation and work to make it better; because whatever you do, DO NOT LET THEM LEAVE AND KEEP THAT GUEST BILL OPEN.

We were more than happy to provide a compensation if it meant they were going to continue spending $200 – sometimes up to $500 a night for a guest room. Then it dawned on me, perhaps this was the same mindset of the administrators. One, don’t take things personally, we in administration make the decisions. Two, they are unhappy students, we are quite comfortable. Three, offer some form of compensation have it be words or a pizza party; because whatever you do, DO NOT LET THEM LEAVE AND TAKE THEIR TUITION DOLLARS ELSEWHERE. I gained a new perspective of the administrators, as it very well may have been the case, they didn’t see the students as students wanting to learn; rather, guests in a hotel adding to revenue generation. This is the basis for the commodification of higher education.

What is Commodification

Within a general economic system, commodification is the transformation of goods, services, ideas, personal proclivities, and anything and everything into objects of economic trade and commodity. Commodification is commonly used in Marxist literature and by critical theorists to explain the commodification of human nature and the soul as things that are traded in a capitalist system – and only through radical liberation/communism can this change. Sure, the concept of humans throughout history being commodities is a thing, but have been widely prevalent under communist regimes, questioning the validity of the analysis – so a Marxist analysis of commodification results in an end-stage contradiction.

The economic framework is perhaps the best framework to understand this; after all, we are trying to figure out what is going on in universities, and Part I was a primer to show the importance of economics and the exchange of dollars and cents in the higher education system. Students are big money makers for universities, this is not a secret, given that every university financial report will show most of their gross revenue comes in from tuition dollars; thus, the economic exchange is established “a good for a price paid.” It brings into question if this was always the case? Well of course it was, students have been paying to go to higher education for as long as they have been around (at least in North America) as higher education is not a requisite for students after high school. It is merely a choice whether someone wants to pursue a specific academic discipline – we may call this a consumer choice.

That is why the high school diploma, or the GED is usually the bare minimum requirement for any entry-level labor job, as it shows an employer that the employee has basic rational, analytical, and theoretical knowledge to make minimum wage in the workforce. This was most certainly the case 50 years ago when most of my family and a large section of my hometown graduated with a high school diploma and got a job working the lines at the automotive plant. However, is this still the case today?

CBS reported in 2019 that the value of a high school degree has collapsed since the 1980s with the average income of high school graduates falling by 12%. This is in contrast to advanced degree holders (associate degrees, bachelors) who have garnered an 18% increase over the same time. Although CBS concludes that a “wealth tax” might be needed – which is lazy analysis, they do provide interesting data on why this may be the case. One point that stuck out is the loss of manufacturing jobs to countries like China and Mexico at the hands of globalist leaders in government and industry, largely after 1989 and the fall of the Soviet Union. Cheaper labor, lower standards, and a lack of private sector unions had CEOs licking their chops at the prospects of moving companies overseas as it was a cheaper alternative to keeping them in North America. This is all but reflected in a Canadian study in 2006 showing that the unemployment rate for someone with a high school diploma was 7.3% as opposed to 4.5% for a bachelor’s and above. Colleges and universities have what we call in the economic world a competitive advantage, or a value proposition – meaning they have what individuals desire to the point of a need. After all, individuals need to work to keep food in the fridge and a roof over their head, so the proposition that you need a job is a key advantage for colleges and universities, and they understand that the fall in value of a high school diploma runs opposite to the rise of tuition rates since the 1980s.

I don’t know how to look at this? As someone with an advanced degree, I am happy that I got it and my financial and economic prospects look bright, but it makes me wonder if I was – in a sense – forced to get this degree lest I swim in the vast sea of precarious employment and low living standards.

You may be thinking, why would this make the universities cower to students like in the case of Evergreen? Why wouldn’t the school do its best Henry Hill’s impression from Goodfellas “Don’t like your classes and unsure about your prospects? F*** you, pay me!” Well perhaps if you are running a criminal organization, where your clients know the rules of the game. However, universities run like Fortune 500 businesses, collecting vast wealth from patrons while praising them for being great consumers of the product. Coca-Cola is not breaking knees with bats, have you ever been on a business trip where one company is looking to go into business with you? You start to question, am I the king of Coca-Cola because I’m sure getting treated like it? But as you know that all stops if the deal falls through and you don’t provide some sort of trade value; similar to universities, once the tuition stops, so does the serviceable warmth and hospitality.

As a student, you are the commodity, you are not a young brain to be molded, you are a means to profit maximization, and by retaining you until you get your bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, or doctorate – they are maximizing their commodity to the fullest extent. I would like to hear about some of the reply emails sent when you get an Alumni donation email in the future.

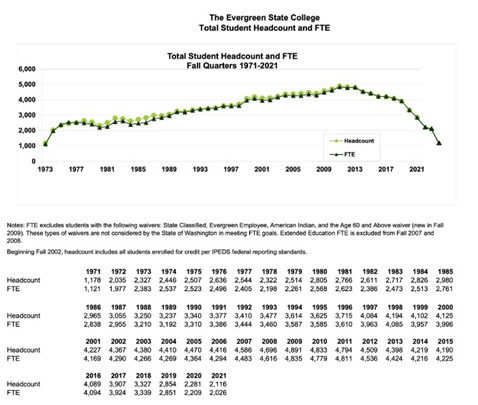

You can see why the administrators kept their mouths shut, so they can keep their mouths open when the profits come in and the students don’t drop out – because they feel a false sense of empowerment. That is why going back to @BenjaminABoyce I was so happy to hear after the Evergreen fiasco in 2017, the school saw a sharp decline in enrolment meaning a sharp decline in tuition gross profits. According to the school’s statistics, enrolment fell 18% from 2017 to 2018. 2020 did not look much better as Evergreen’s financial statements mention the continuing decrease in tuition revenue due to declining enrolment. The summary statement for the most recent report is as follows:

“Enrollment has been declining for the past several years which the College is addressing through the implementation of a robust three-year renewal plan. However, if enrollments continue to decline the College could continue to experience a decline in tuition revenue.” (page 14).

The data displayed on a graph is shocking, as the current enrolment in 2021 seems to have dropped anywhere from 45% – 53% since the issues in 2017 (see graph below). In a way Evergreen has been proving my thesis wrong as pandering to these students did not achieve retention and enrolment, perhaps it is a sign that prospective students are more adept at the role universities are playing and making informed decisions against the cultural insanity of today’s universities.

So, are there other reasons why universities would still be pandering to students in this way, given the failure of Evergreen, most presidents, provosts, and deans would be wary to consider the Evergreen path given their growth model? With that said, there can be more factors than money, two that seem to stand out to me through my engagement with administration and that is a legal liability and retaining an unsustainable growth model.

Legal Liability Shield

In 2021, I engaged in some prospective research on the infantilization of students in higher education. One of the implications of the negative outcomes of infantilization is the lack of accountability from institutions and protect themselves from a lawsuit from one side or another. For example, say a student wants to sue the school for obtaining a degree that is lowly in the job market, the university can turn back around and say they provided the resources and the opportunity to get the job, but they ultimately are held unaccountable to your outcomes in the job market. It is much like the hotel bellman who put a bag in a guest’s car awkwardly, and while the guest was driving the bag fell over breaking an expensive glass. Well, the hotel is not at fault because they are protected against any liability off the ground or through unintended actions. Furthermore, the gray area of describing the awkward placement of luggage.

In a way, we can say that colleges and universities are acting as a casino, where the house always wins. They actively commodify students in a win-win situation, either they graduate and find a job earning tuition dollars, or they graduate and don’t find a job because of poor market prospects seen by the university, but not expanded upon, or they don’t graduate but still have to pay for semesters that they did take with no outcome of a degree. I don’t have an answer to what can be done as a remedy, except for pointing this out and potential legislative change.

An Unsustainable Growth Model

Colleges and universities practice an unsustainable growth model, this is no secret since the Times Higher Education produced a report showing that many respondents – most of the higher education administrators – feel the university business model is unsustainable and will encounter problems within the next 10 years. Further findings suggest that a large majority of staff members feel universities are behind in administrative aspects like modernization of services, financing issues, flat demographic trends in high school graduates, negative public perception of tuition, and questioning the value of higher education in modern society. Both the demographic trends and value of higher education seem to be key drivers in how universities want to grow, but the demand and supply are not there – this leads to hemorrhaging of money.

A prime example of hemorrhaging money, I took a class in university, a sociology class, where it was me and 6 other students in the classroom, the professor was tenured. I once asked if there is another section of this class to which the professor said “yes”. I asked why not merge the classes, to which she responded that it was better for learning outcomes that the students get more focus and allow us to offer more authentic assessments. Sure, that is a nice response, but financially it seems like a nightmare. Let’s break down the numbers, if two tenured professors are teaching two sessions, they purposely cap the classes for desired learning at let’s say 10. So, at the most let’s say 2 tenured professors, and 16 students in a semester.

- 2 tenured professors at an avg. salary of 130,000 = $260,000

- We can halve this salary considering this reflects only one semester out of the two so $130,000.

- 16 students at an avg. semester tuition in Canada $3,500 = $56,000.

So, if we have two teachers making $65,000 per semester ($130,000), with a total tuition revenue for this class bringing in only $56,000. For that one class in one semester, that school is losing $74,000. Now there are variables here, usually, a professor has three classes per semester, which means they are making up the money for other classes, I will grant that. But even if it is not as bad as this example, close to breaking even, or this is in multiple classes across the campus. This can spell big trouble for universities, and the student holding the burden of future debt, but hey, every commodity has a lifespan to maximize its potential.

I hope part two was not too frustrating given that universities have shifted from an institute of higher learning to a trading commodity index – rest assured, change has been in the works and discussions are happening, the thing that troubles me the most, is that this is a messy problem with a lot of moving parts, and I just think it will be a long time to find an answer. For the third and final part of this little series, we will talk about culture and the socio-political implications on higher education culture.

2 thoughts on “What is Going on in Universities? Student Debt, Commodification, and the Socio-political Landscape. Part II: Commodification: Are they Students or Customers?”